Advice on Solving Cold Cases from Someone Who's Worked on Hundreds

- Andrea Cipriano

- Jul 4, 2019

- 5 min read

Updated: Jul 6, 2019

"This isn't like television where you can solve a decades-old homicide case in 45 minutes with three commercials," said Joseph Giacalone, retired NYPD Sergeant and former Commanding Officer of the Bronx Cold Case Squad, to the audience attending his CrimeCon: On The Run lesson.

When someone is murdered, police go through the same routine to catch the killer. They collect evidence at the scene, canvas the neighborhood, interview witnesses, make an arrest, and close the case before moving onto the next one.

But, sometimes, that perfect routine doesn't go as smoothly as the investigators had hoped. Leads don't pan out, witnesses aren't helpful, DNA doesn't match anyone in the system, and the killer gets away with it.

Then, the unsolved murder gets 'caught' by a detective in a Cold Case Squad.

There are about 185,000 unsolved homicides nationwide, with an average of 90,000 people missing at any given time, according to the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System.

With the mountain of 10,000 unsolved homicides in New York City alone, Giacalone, who is also an adjunct professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, is no stranger to this burden.

"These cases are piling up left and right – it's actually a national emergency that no one wants to talk about," he said.

Even more staggering, it's estimated that 150 – 200 cases are added every year to the stack of 10,000 files already collecting dust. Giacalone's work feels like an uphill battle that the public may never understand.

During his lesson, Giacalone reminded the CrimeCon audience, who probably knew this better than anyone, that TV shows like NCIS don't reflect reality. You need more than a latent fingerprint or a strand of hair to solve a murder that took place decades earlier.

Giacalone emphasized the uphill battle by explaining, "You don't have all of the things you get when you're working a fresh homicide – we're missing all that. We don't have a crime scene. We're picking this up out of a box!"

Man, I really wish he was kidding.

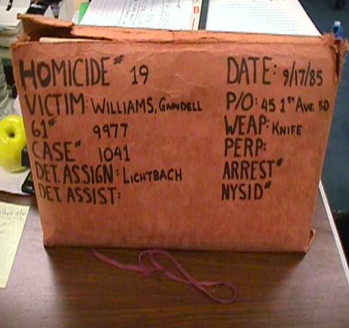

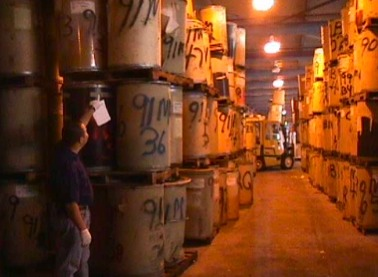

Above are photos from Stacy Horn's novel, "The Restless Sleep," which also narrated the difficulties of working in an NYPD Cold Case Squad.

The first image is what a typical cold case file would look like when a detective would 'catch a case' — it's old, beaten up, and not well sealed meaning papers or documents could've been lost and damaged over time.

The second image is of an NYPD Property Clerk warehouse in Queens. Each barrel spray painted with a location code contains homicide evidence.

If you're requesting information on a cold case from the Property Clerk (a.k.a., the DMV of the NYPD), regardless of who you are, don't get your hopes up believing that you're going to get anything in a timely manner. For reference, the 3 offices listed on Google have an average review of 1.13 stars.

It's no wonder cold case detectives get burnt out over time.

In terms of my own experience, I had the amazing and formative opportunity a few years ago to spend some time with the Brooklyn Cold Case Squad in Downtown Brooklyn. The detectives there are incredibly hardworking, and they truly put their hearts into every case they look at — even when handeling multiple at a time.

The memory that sticks out to me the most is the endless rows and rows of filing cabinets that hugged the office walls. The main floor was so cluttered that they had filing cabinets in the free space of the women's bathroom. If even a fraction of those drawers were filled with unsolved cold cases, you're talking about thousands.

How can you help?

With the true crime genre soaring in popularity, there are more "9 to 5 job-by-day, citizen detective-by-night" individuals taking a crack at solving cases — and Giacalone welcomes it.

"We often rely on the public to help us find answers and bring closure to these families," he said. "But be aware, you know just as much about the case as the police do; you're all starting from scratch."

Giacalone began by explaining that the first thing police and citizen detectives need to think about when looking over a cold case is: Could this be connected to something else?

According to Giacalone, this thinking could lead to the the infamous S----- word that no police department wants to hear: serial, serial killer, serial rapist, etc. While discovering a string of murders committed by the same person isn't impossible, don't be surprised by the amount of pushback recieved from the public or law enforcment if you declare you've found a connection.

One of the ways to check for these kinds of crimes includes looking at statistics over time. An excellent tool for that is the Uniform Crime Report database where you can search for incidents that go as far back as 1960 while filtering for location and type of offense.

Individuals can also look through newspaper articles and check out the archives (like The New York Times Archives), either to find connected cases or new evidence altogether.

To the older audience in the room, Giacalone posed the question, "Anyone remember Microfiche?" Everyone laughed in response. (For the readers my age, microfiche is when journal articles were scaled-down and printed on film. You'd have to look at them through a special device to read the documents.) He followed up by keeping a light tone, and saying, "No more of that stupid thing you could never line up. You can find any article in any newspaper that was ever created."

Giacalone is right. The advancements in technologies haven't just helped police departments — it's opened avenues for anyone to dig online for answers.

Speaking of digging online, Giacalone mentioned that one of the most underrated tools in cold case investigations is, put simply, the internet.

"Police Departments are finally using social media to make Facebook pages to put information up and find things out," he said.

This is something the public can be doing as well. The more people talking about a case to help spread awarness and get it solved, the better.

Finally, one of the most essential things needed for solving cold cases is willpower. More often than not, investigators may give up on a case and move on to the next one. Giacalone had worked in the past on reopened homicides that got solved immediately – not because the detectives are "geniuses" — but because the person before them did all the work and gave up on it towards the end.

Giacalone's advice to citizen detectives – if you feel like you're onto to something, don't give up just before you strike gold.

Other useful websites Giacalone mentioned during his lesson are:

MurderData.org information on over 800k U.S. homicides (updates regularly).

NamUs.gov information on missing, unidentified, and unclaimed persons in the U.S.

Uniform Crime Report database FBI's list of state and local police dept. data

The New York Times Archives 13 million articles from January 1, 1923 through December 31, 1980.

A website I personally use:

CharleyProject.org information on over 13,000 U.S. Cold Cases.

To learn more about Joseph Giacalone, his website can be found here.

His book, The Criminal Investigative Function: A Guide for New Investigators can be found at the link provided.

This is a condensed version of what I learned and took away from the hour-long event mentioned above which I attended during CrimeCon, presented by Oxygen.

Comments